Practicing for People We Will Never Meet

- drjaleesrazavi

- Dec 24, 2025

- 2 min read

Occupational Medicine and Generational Impact

Occupational Medicine is not a specialty of moments.

It is a specialty of generations.

Since my last post on this topic, I have received several messages asking why I continue to frame Occupational Medicine in generational terms—and why this distinction matters. The short answer is that if we misunderstand the time horizon of this discipline, we misunderstand its purpose, its value, and ultimately its ethical mandate.

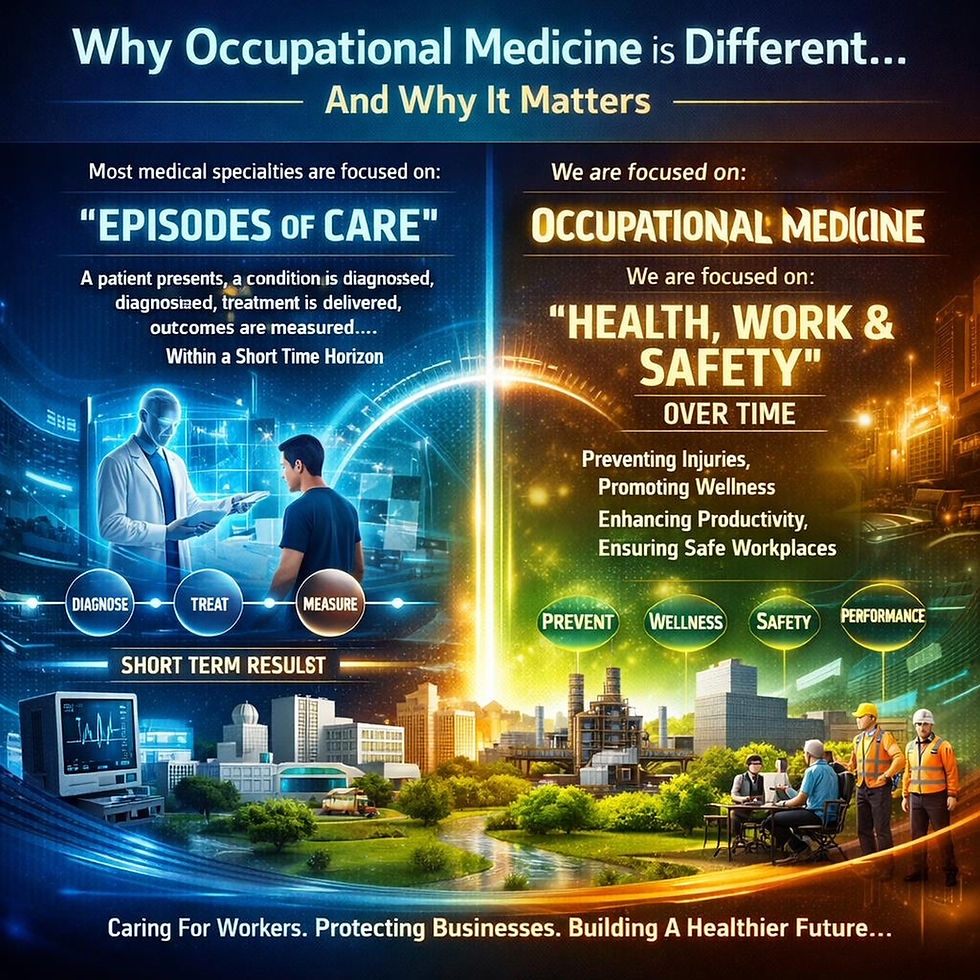

Most medical specialties are organized around episodes of care. A patient presents with symptoms, a diagnosis is established, treatment is delivered, and outcomes are measured over weeks, months, or occasionally years. This model is entirely appropriate for many disciplines and has produced extraordinary advances in modern medicine.

Occupational Medicine operates on a fundamentally different axis.

Our unit of analysis is not only the individual worker in front of us, but the work system itself: the task, the exposure profile, the physical and psychosocial demands, the organizational structure, the controls in place, and—most critically—the timeline over which harm or protection unfolds. The health effects we assess and attempt to prevent often accumulate slowly and silently over decades. Noise exposure, chemical agents, ergonomic strain, shift work, fatigue, and chronic psychosocial stress do not conform to claim periods, fiscal quarters, or retirement milestones.

When Occupational Medicine is practiced properly, its greatest successes are rarely dramatic or immediately visible. They do not present as heroic rescues or rapid recoveries. Instead, they appear years later as outcomes that never materialize: cancers that do not develop, hearing loss that does not occur, chronic pain that never becomes disabling, and workers who reach retirement with their health, dignity, and function intact.

This is precisely why measuring the value of Occupational Medicine solely through short-term metrics—claims closed, costs reduced, or days lost—fundamentally misunderstands the discipline. Those measures capture administrative activity, not preventive impact. They record what has already gone wrong, not what has been successfully prevented.

This is what makes Occupational Medicine a generational specialty.

Decisions made today about exposure limits, job design, fatigue management, reporting structures, or psychosocial risk controls shape the health trajectories of workers who

may not yet have entered the workforce. The beneficiaries of good Occupational Medicine practice are often unknown to us by name. In many cases, they are not yet employees. In some cases, they are not yet adults.

To practice Occupational Medicine responsibly is therefore to accept a moral contract with the future. We are accountable not only to the workers we assess today, but to those who will inherit the systems we help design, approve, or challenge. That obligation requires long memory, professional independence, and the willingness to advocate for prevention even when its benefits will be realized long after current leadership has moved on.

In the next post in this short series, I will expand this generational lens beyond physicians to the entire occupational health ecosystem—and explain why terms such as Generations Physician or Generations Occupational Health Professional are not rhetorical flourishes, but accurate descriptions of what this work truly demands.

Comments